- Home

- Ferguson,Rachel

A Footman for the Peacock

A Footman for the Peacock Read online

Rachel Ferguson

A Footman for the Peacock

The peacock displayed himself and paraded the lawn, sometimes pausing to look up at the sky.

Waiting? Listening? Guiding. No. Signalling.

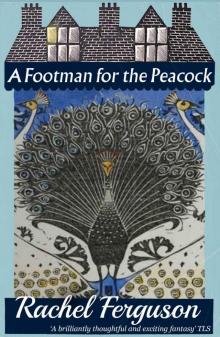

Controversial when first published in the early days of World War II, due to its treatment of a loathsome upper-crust family dodging wartime responsibility, A Footman for the Peacock can now be enjoyed as a scathing satire of class abuses, a comic masterpiece falling somewhere between Barbara Pym and Monty Python.

Sir Edmund and Lady Evelyn Roundelay live surrounded by a menagerie of relations and retainers. The Roundelays’ history of callous cruelty is literally etched on a window of the servants’ quarters with the words “Heryn I dye, Thomas Picocke. 1792”. Sir Edmund reflects cheerfully on the running footmen who have ‘died off like flies’ in the family’s service.

But now—amidst digressions on everything from family history and servant woes to the villagers’ linguistic peculiarities and a song immortalizing the footman’s plight—war threatens the Roundelays’ smug superiority. What’s more, it appears that the estate’s peacock is a reincarnation of Thomas Picocke, and may be aiding the Nazi cause … By turns giddy and incisive, hilarious and heartbreaking, A Footman for the Peacock is Rachel Ferguson at her very best. This new edition features an introduction by Elizabeth Crawford.

‘The Roundelays are people to live with and laugh at and love’ Punch

FM1

To

ARABELLA TULLOCH

Who as singer, comedienne, and conversationalist, delights me equally

CHRISTINE CAMPBELL THOMSON

Who at all times can believe in as many as three impossible things before breakfast

and

ANTHONY ARMSTRONG

(‘A.A.’ of Punch)

Best of company, kindest of friends, Who once christened a gargoyle of a Vulture on Notre Dame ‘The Very Reverend Pontifex Cardew’

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page/About the Book

Dedication

Contents

Introduction by Elizabeth Crawford

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER IV

CHAPTER V

CHAPTER VI

CHAPTER VII

CHAPTER VIII

CHAPTER IX

CHAPTER X

CHAPTER XI

CHAPTER XII

CHAPTER XIII

CHAPTER XIV

CHAPTER XV

CHAPTER XVI

CHAPTER XVII

CHAPTER XVIII

CHAPTER XIX

CHAPTER XX

CHAPTER XXI

CHAPTER XXII

CHAPTER XXIII

TAILPIECE

About the Author

Titles by Rachel Ferguson

Furrowed Middlebrow Titles

Evenfield – Title Page

Evenfield – Chapter I

Copyright

Introduction

A FAMILY – a House – and – Time. These are the ingredients whipped by Rachel Ferguson (1892-1957) into three confections – A Harp in Lowndes Square (1936), A Footman for a Peacock (1940), and Evenfield (1942) – now all republished as Furrowed Middlebrow books. Her casts of individuals, many outrageous, and families, some wildly dysfunctional, dance the reader through the pages, revealing worlds now vanished and ones that even in their own time were the product of a very particular imagination. Equally important in each novel is the character of the House – the oppressive family home of Lady Vallant in A Harp in Lowndes Square, comfortable, suburban Evenfield, and Delaye, the seat of the Roundelays, a stately home but ‘not officially a show place’ (A Footman for a Peacock). Rachel Ferguson then mixes in Time – past, present, and future – to deliver three socially observant, nostalgic, mordant, yet deliciously amusing novels.

In an aside, the Punch reviewer (1 April 1936) of A Harp in Lowndes Square remarked that ‘Miss Ferguson has evidently read her Dunne’, an assumption confirmed by the author in a throwaway line in We Were Amused (1958), her posthumously-published autobiography. J.W. Dunne’s Experiment with Time (1927) helped shape the imaginative climate in the inter-war years, influencing Rachel Ferguson no less than J.B. Priestley (An Inspector Calls), John Buchan (The Gap in the Curtain), C.S. Lewis, and J.R.R. Tolkien. In A Harp in Lowndes Square the heroine’s mother (‘half-educated herself by quarter-educated and impoverished gentlewomen’) explains the theory to her children: ‘… all time is one, past, present and future. It’s simultaneous … There’s a star I’ve heard of whose light takes so many thousands of years to reach our earth that it’s still only got as far along history as shining over the Legions of Julius Caesar. Yet that star which is seeing chariot races is outside our window now. You say Caesar is dead. The star says No, because the star’s seen him. It’s your word against his! Which of you is right? Both of you. It’s only a question of how long you take to see things.’ The concept of ‘simultaneous time’ explains why the young first-person narrator, Vere Buchan, and her twin brother James, possessing as they do ‘the sight’, are able to feel the evil that haunts their grandmother’s Lowndes Square house and uncover the full enormity of her wickedness. In A Footman for a Peacock a reincarnation, one of Time’s tricks, permits a story of past cruelty to be told (and expiated), while Evenfield’s heroine, Barbara Morant, grieving for her mother, takes matters into her own hands and moves back to the home of her childhood, the only place, she feels, ’where she [her mother] was likely to be recovered.’

For 21st-century readers another layer of Time is superimposed on the text of the novels, now that nearly 80 years separates us from the words as they flowed from the author’s pen. However, thanks to We Were Amused, we know far more about Rachel Ferguson, her family, and her preoccupations than did her readers in the 1930s and early 1940s and can recognise that what seem whimsical drolleries in the novels are in fact real-life characters, places, and incidents transformed by the author’s eye for the comic or satirical.

Like Barbara Morant, Rachel Ferguson was the youngest of three children. Her mother, Rose Cumberbatch (probably a distant relation to ‘Benedict’, the name ‘Carlton’ appearing in both families as a middle name) was 20 years old when she married Robert Ferguson, considerably older and a civil servant. She was warm, rather theatrical, and frivolous; he was not. They had a son, Ronald Torquil [Tor] and a daughter, Roma, and then, in 1892, after a gap of seven years, were surprised by Rachel’s arrival. When she was born the family was living in Hampton Wick but soon moved to 10 Cromwell Road, Teddington, a house renamed by Mrs Ferguson ‘Westover’. There they remained until Rose Ferguson was released from the suburban life she disliked by the sudden death of her husband, who was felled by a stroke or heart attack on Strawberry Hill golf course. Fathers in Rachel Ferguson’s novels are dispensable; it is mothers who are the centres of the universe. Rose Ferguson and her daughters escaped first to Italy and on their return settled in Kensington where Rachel spent the rest of her life.

Of this trio of books, Evenfield, although the last published, is the novel that recreates Rachel Ferguson’s earliest years. Written as the Blitz rained down on London (although set in the inter-war years) the novel plays with the idea of an escape back into the security of childhood, For, after the death of her parents, Barbara, the first-person narrator, hopes that by returning to the Thameside suburb of ‘Addison’ and the house of her childhood, long since given up, she can regain this land of lost content. The main section of the novel describes the Victorian childhood she had enjoyed while living in ‘Evenfield’, the idiosyncrasies of family and neighbours lovingly r

ecalled. Incidentally, Barbara is able to finance this rather self-indulgent move because she has made a small fortune from writing lyrics for successful musical comedies, a very Rachel Ferguson touch. What might not have been clear to the novelist’s contemporaries but is to us, is that ‘Addison’ is Rachel Ferguson’s Teddington and that ‘Evenfield’, the Morant family home, is the Fergusons’ ‘Westover’. In We Were Amused Rachel Ferguson commented that since leaving Teddington ‘homesickness has nagged me with nostalgia ever since. I’ve even had wild thoughts of leasing or buying Westover until time showed me what a hideous mistake it would prove’. In writing Evenfield Rachel Ferguson laid that ghost to rest.

But what of the ghost in A Harp in Lowndes Square? Vere senses the chill on the stairs. What is the family mystery? Once again Rachel Ferguson takes a fragment of her family story and spins from it what the reviewer in Punch referred to as ‘an intellectual ghost story’. The opening scene, in which a young girl up in the nursery hears happy voices downstairs, is rendered pathetically vivid by the description of her frock, cut down from one of her mother’s. ‘On her small chest, the overtrimming of jetted beads clashed …’. This humiliation, endured not because the family lacked funds, but because the child’s mother cared nothing for her, was, Rachel Ferguson casually mentions in We Were Amused, the very one that her own grandmother, Annie Cumberbatch, inflicted on her daughter Rose. ‘The picture which my Mother drew for me over my most impressionable years of her wretched youth is indelible and will smoulder in me till I die.’ Rachel Ferguson raised the bar by allotting Sarah Vallant a wickedness far greater than anything for which her grandmother was responsible, but it is clear that she drew her inspiration from stories heard at her own mother’s knee and that many of the fictional old lady’s petty nastinesses – and her peculiarly disturbing plangent tones – were ones that Rachel Ferguson had herself experienced when visiting 53 Cadogan Square.

The Punch reviewer noted that in A Harp in Lowndes Square Rachel Ferguson demonstrated her ‘exceptional ability to interpret the humour of families and to make vivid the little intimate reactions of near relations. Children, old people, the personalities of houses, and the past glories of London, particularly of theatrical London, fascinate her.’ Rachel Ferguson’s delight in theatrical London is very much a feature of A Harp in Lowndes Square, in the course of which Vere Buchan finds solace in a chaste love for an elderly actor (and his wife) which proves an antidote to the wickedness lurking in Lowndes Square. As the reviewer mentioned, old people, too, were among Rachel Ferguson’s specialities, especially such impecunious gentlewomen as the Roundelay great-aunts in A Footman for a Peacock, who, as marriage, their only hope of escape, has passed them by have become marooned in the family home. Each wrapped in her own treasured foible, they live at Delaye, the house inherited by their nephew, Sir Edmund Roundelay. The family has standing, but little money. Now, in the early days of the Second World War, the old order is under attack. Housemaids are thinking of leaving to work in the factories and the Evacuation Officer is making demands. ‘You are down for fifteen children accompanied by two teachers, or ten mothers with babies, or twenty boys or girls.’ This is not a world for which the Roundelays are prepared. Moreover other forces are at work. Angela, the sensitive daughter of the family, watches as, on the night of a full moon, Delaye’s solitary peacock puts on a full display, tail feathers aglow, and has an overpowering feeling he is signalling to the German planes. What is the reason for the peacock’s malevolence? What is the meaning of the inscription written on the window of one of the rooms at the top of the house: ‘Heryn I dye, Thomas Picocke?’ In We Were Amused Rachel Ferguson revealed that while staying with friends at Bell Hall outside York ‘on the adjoining estate there really was a peacock that came over constantly and spent the day. He wasn’t an endearing creature and … sometimes had to be taken home under the arm of a footman, and to me the combination was irresistible.’ That was enough: out of this she conjured the Roundelays, a family whom the Punch reviewer (28 August 1940) assures us ‘are people to live with and laugh at and love’ and whom Margery Allingham, in a rather po-faced review (24 August 1940) in Time and Tide (an altogether more serious journal than Punch), describes as ‘singularly unattractive’. Well, of course, they are; that is the point.

Incidentally Margery Allingham identified Delaye ‘in my mind with the Victoria and Albert’, whereas the 21st-century reader can look on the internet and see that Bell Hall is a neat 18th-century doll’s house, perhaps little changed since Rachel Ferguson stayed there. Teddington, however, is a different matter. The changes in Cromwell Road have been dramatic. But Time, while altering the landscape, has its benefits; thanks to Street View, we can follow Rachel Ferguson as, like Barbara Morant, she pays one of her nostalgic visits to ‘Evenfield’/’Westover’. It takes only a click of a mouse and a little imagination to see her coming down the steps of the bridge over the railway line and walking along Cromwell Road, wondering if changes will have been made since her previous visit and remembering when, as a child returning from the London pantomime, she followed this path. As Rachel Ferguson wrote in We Are Amused, ’I often wonder what houses think of the chances and changes inflicted on them, since there is life, in some degree, in everything. Does the country-quiet road from the station, with its one lamp-post, still contain [my mother’s] hurrying figure as she returned in the dark from London? … Oh yes, we’re all there. I’m certain of it. Nothing is lost.’

Elizabeth Crawford

CHAPTER I

1

THERE are country houses and country houses.

There is the type of mansion where the wrong kind of guest tips the staff too much and is regretfully dissected in the servants’ hall as his car slides off down the avenue, and there is the mansion where the right kind of guest is hardly able to tip the staff at all, and for whom the butler and footman continue to feel a warm affection.

There are houses, manors, halls, granges and abbeys in which Queen Elizabeth is known to have slept, and a larger number from which sheer lack of time compelled the indefatigable recumbent to abstain. There are country seats that get illustrated in Country Life, or pass, via midnight smart set pillow-fights, into The Police News and the divorce courts, and others possessing a priest’s hole but no ghost: an oubliette and ghost but no hidden treasure: a moat and no muniment room: a plentiful staff but no mention in Domesday Book, or Saxon ruins in the Home field and no butler at all.

There are denes, priories, castles and manors, in the rooms, galleries and grounds of which Catherine Howard still screams and Jane Grey had pricked her finger, Bloody Mary exclaimed ‘God’s death!’ Raleigh had smoked the first pipe of tobacco, Charles the Second hidden in an oak tree, someone else had signed something historic and damaging, Barbara Castlemaine had threatened to throw herself out of the window and Prince Arthur had actually done so: where the Queen of Scots had given away trinkets to faithful retainers and Wolsey had had all his taken from him. And there are English families with fairy banners and ‘lucks’ famed in ballads, and others of equally ancient lineage and no luck at all. One contingent still entertains the autumnal shooting party and is pictured in the papers filing like portly Sherlock Holmeses across the moors, while the second party emerges from posterns at sunset and hopefully pops away at rabbits for the larder on their own mortgaged acres.

And somewhere in England, in rating between the extremes of screaming queen and the pedigree’d pursuit of pot-luck, stands Delaye, seat of the Roundelays, presently occupied by Sir Edmund Roundelay, his family and various collaterals.

2

Delaye is not officially a show place, mainly because the family recoils from exposing portions of their home for gain, love or charity, to that mythical trio, Tom, Dick or Harry. Inevitably, the polite and the genuine enthusiast alike have made the suggestion, backed by those who see in the arrangement a sensible source of profit to an overtaxed landlord which should also be educative to the bourgeois sightseer and teach

his descendants — who knows? — that the fourteenth-century refectory table is not a mere surface for the carving of initials. But Sir Edmund, brushing aside the notion, would merely answer with the unfinished sentence that silenced without convincing ‘. . . playing darts on the tapestry . . .’

Delaye does not possess any objects which could be actually labelled as priceless, but its furniture and the tapestry alone would make a very fair sum at Christie’s, and if the portraits are not a galaxy of old masters, of the type that biographers write in for permission to reproduce in their Lives of Caroleans and Tudors, it possesses a respectable quota among the latest of which is numbered what Musgrave, the butler, alludes to as ‘The Hair-Comber’, as he cleanses the canvas half-yearly with a raw potato.

The principal rooms are always chilly and can be enjoyed only in a virulent heat-wave. Their windows all face north, as the direct result of that conventional parental gesture which sent its sons, on completing their education, to make the Grand Tour, a journey which commonly took in Italy, with an admiration real or inculcated of its architecture, and that was to be responsible on their return for north lights in two-fifths of the mansions of England, from a universal overlooking of the fact that the climate of the British Isles was not that of southern Europe. Thus, since the eighteenth century, from early spring to the following winter, the drawing-rooms and boudoirs were invaded once a day (and four times in the cold months) by a file of menservants, the firelight twinkling on their crimson plush and smiting flashes from their aiguillettes, bearing logs and brass scuttles of coal.

In the first-floor corridor there still stands in a dark recess a log-boy’s stool, relic of the life of some small disregarded member of the staff, whose duty it was to time by an hourglass the exact minute at which the next load must be fetched and carried.

Evenfield

Evenfield A Footman for the Peacock

A Footman for the Peacock